13 in (33 cm) high

cf. Lawrence Smith, Victor Harris and Timothy Clark, Japanese Art: Masterpieces in the British Museum, 1990, p.162, no. 152

Gallé and Japonisme, exh. cat., Suntory Museum of Art, Osaka, 2008, no.90

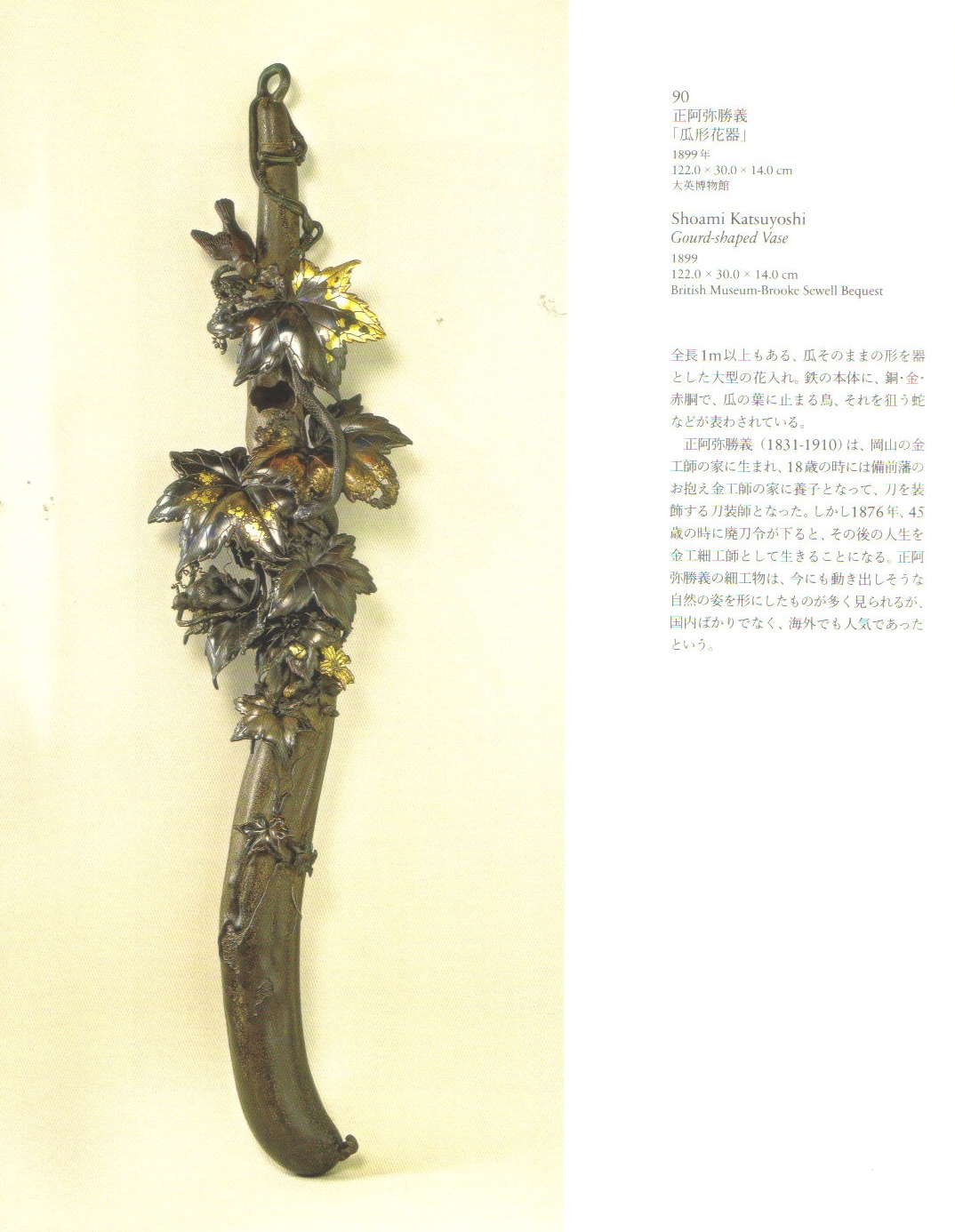

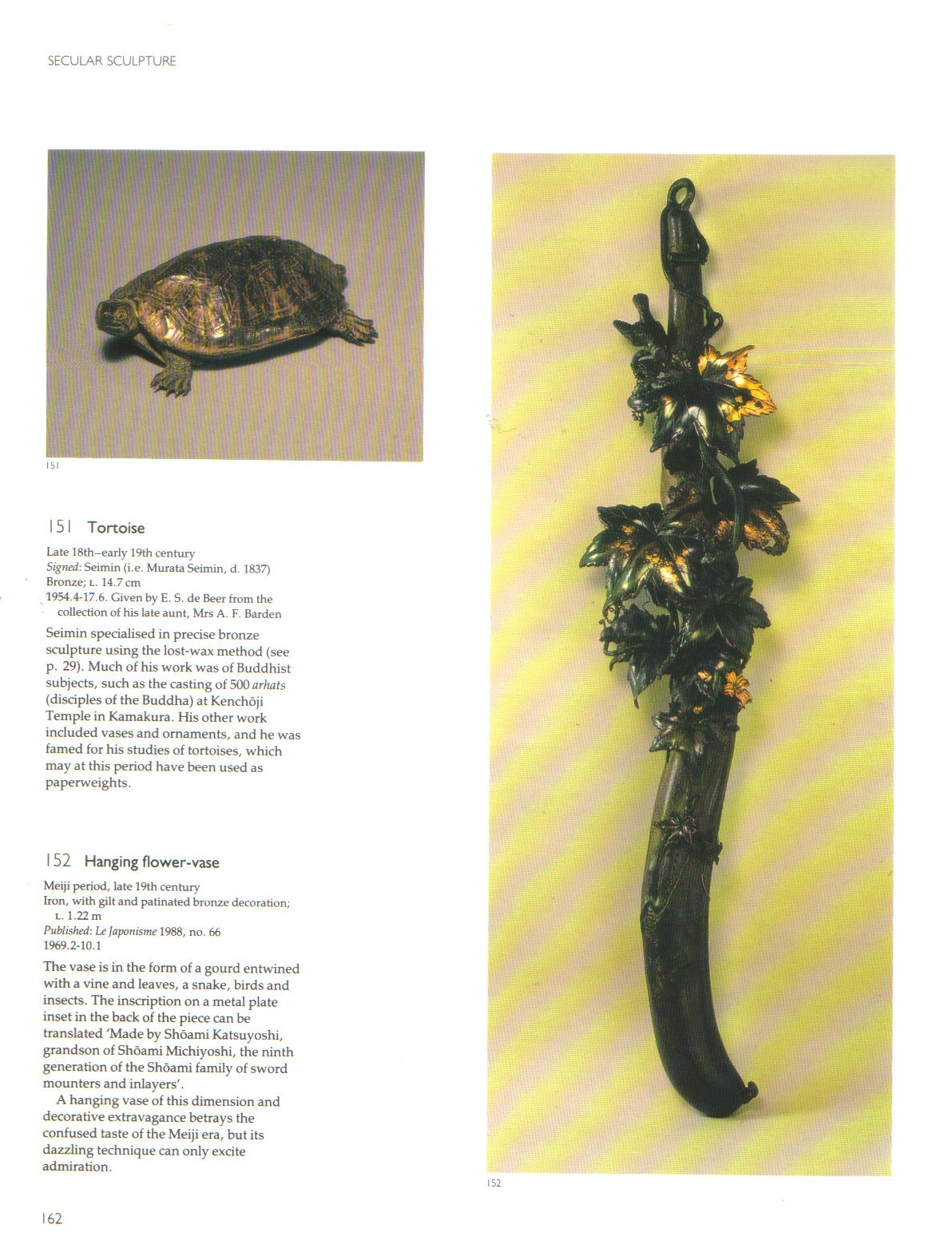

Traditionally, a Japanese samurai warrior wore two swords as a badge of rank, and over the centuries craftsmen had developed the decoration of these swords and their fittings (tsuba) into a fine art in itself. These fittings were often cast in bronze and decorated with inlays of patinated alloys. The most popular of these alloys were shibuichi, which was grey or green, and shakudo, which could be pickled to a rich black, said to resemble ‘the colour of a crow’s wings in the rain’. These pieces were further embellished by inlays of gold, silver, and copper.

However, after the Meiji Restoration, the samurai were gradually stripped of their powers, and were banned from wearing swords in 1876. With the domestic market for their art gone and faced with an unfamiliar and competitive international trading market, traditional craftsmen found their livelihood potentially in danger. But in fact their skills became a key part of Japan’s highly successful export trade to western markets.

Shōami Katsuyoshi was one of the many metalworkers specialised in the crafting of tsuba who turned his hand to a new form of art. Born in 1832 in Nakagawa, Katsuyoshi was adopted at the age of 18 by the Shōami Fujishiro family. They were sword-mounters, and he eventually became the ninth and last master of that family. After 1876, he began to create okimono or bronze sculptures. These were purely decorative pieces with no practical use, and were for the most part a novelty in Japanese art. In the Meiji period, however, they flourished and came to be highly valued both by foreign buyers, and in Japan itself. Valued for his excellence in craftsmanship and metalworking skills, Katsuyoshi was commissioned to make pieces for the Imperial family. This gourd vase is considered to be one of his most important and unusual pieces. A closely similar piece by him, a hanging-flower gourd vase, may be found in the British Museum. In addition, the Okayama Prefectural Museum in Japan includes many of Katsuyoshi’s finest works. Another piece, an elephant-shaped incense burner, is featured in the Khalili Collection.

Japanese art influenced European art and design from the 1880s as expressed in the rise of Japonisme and Art Nouveau. This vase represents a fusion of styles: ideas drawn from western ideas of Romanticism and naturalism are combined with traditional Japanese motifs and imagery such as insects, reptiles, and animals, brought to life by Japanese craftsmen using historic techniques.